How to Build an Aerobic Base Without Burning Out

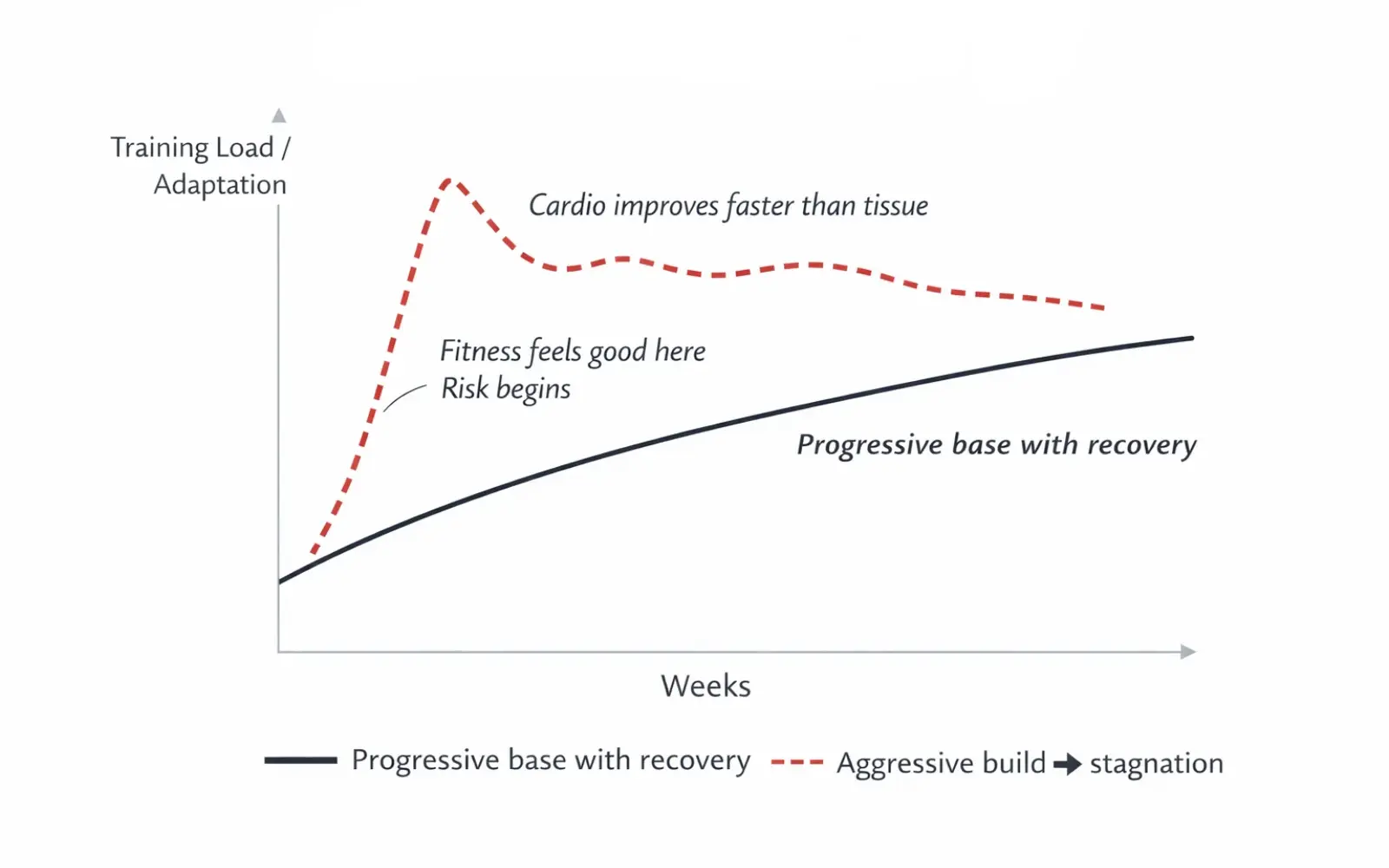

Base building is where durable running fitness is created. It’s the quiet phase—often well before race-specific training—when the body learns to handle volume, recover efficiently, and move economically at low intensity. Done well, it supports everything that follows. Done poorly, it leads to fatigue, stalled progress, or injury before the real work even begins.

The challenge is not effort, but restraint. Structuring base-building weeks with smart progression, planned recovery, and patience is what allows consistency to compound instead of collapse.

The Purpose of the Aerobic Base

An aerobic base reflects how efficiently your body produces energy using oxygen over long periods. Physiologically, it means a stronger heart, a denser network of capillaries supplying working muscles, and an increase in both the number and efficiency of mitochondria—the structures that convert fuel into movement.

These adaptations are slow by nature. They don’t respond well to shortcuts or aggressive timelines. Base building works best when the training load increases gradually enough for the body to adapt without being pushed into constant repair mode.

Structuring the Weeks: Stress That Accumulates, Not Explodes

A typical aerobic base phase lasts 6 to 12 weeks, depending on background fitness and goals. Each week should apply just enough stress to stimulate adaptation while leaving room for recovery.

Start Where You Are

Your starting point is not an ideal mileage number—it’s the highest weekly volume you can currently sustain without lingering soreness, disrupted sleep, or creeping fatigue. That becomes your baseline.

Progress Gradually—and Intentionally

Guidelines like the “10% rule” are useful, but they work best as guardrails, not targets. Some weeks may increase mileage slightly; others may hold steady.

Progression works best when:

- You extend long runs in small steps, typically 1–2 miles at a time

- You add frequency only after the current schedule feels routine

- You resist stacking multiple changes in the same week

It’s worth remembering that the cardiovascular system adapts faster than bones, tendons, and connective tissue. Feeling aerobically strong does not mean your structure is ready for sharp increases in load.

Keep the Effort Truly Easy

Most base-phase runs should sit comfortably in the aerobic zone—roughly 60–75% of maximum heart rate for most runners. Practically, this means running at a pace where conversation feels natural and breathing stays controlled.

If easy runs start to feel like “workouts,” or require focus to maintain, intensity has crept too high. That shift is subtle but costly over time.

Light strides or short pickups can be included to maintain coordination and running economy, but they should feel refreshing—not demanding.

Plan Recovery Weeks

Every three to four weeks, reduce total mileage by 20–30%. These weeks are not interruptions; they are part of the training process. Recovery weeks allow fatigue to dissipate and adaptations to consolidate, making the next block more productive.

The Discipline of Patience

Base building often feels deceptively easy once fitness begins to improve. This is where many runners make their most common mistake: adding tempo runs, harder long runs, or early intensity because “it feels controlled.”

That sense of readiness is often cardiovascular, not structural. The cost of moving too fast rarely appears immediately—it shows up weeks later as stagnation, niggles, or exhaustion.

Patience during base building means trusting delayed rewards. The goal is not to prove fitness now, but to protect the ability to train well later.

Learning to Read the Warning Patterns

Single bad days happen. What matters are trends. Signs that the base phase is drifting toward burnout include:

- Soreness that persists beyond 48 hours, week after week

- Declining pace at the same perceived effort

- Disrupted sleep or rising resting heart rate

- Low motivation for runs that used to feel automatic

- Recurring minor aches that never fully resolve

One symptom in isolation may mean little. Several appearing together over time signal the need to pull back.

An Example 8-Week Aerobic Base Progression

For a runner starting at roughly 20 miles per week:

- Weeks 1–2: 20–22 miles, all easy; long run 6–7 miles

- Weeks 3–4: 24–26 miles; long run up to 8 miles

- Week 5: Recovery week—20 miles; long run 6–7 miles

- Weeks 6–7: 26–28 miles; long run up to 9 miles

- Week 8: Recovery week—22 miles

From here, mileage can continue to rise conservatively, or training can transition toward moderate intensity with a stable aerobic foundation in place.

A Base That Lasts

Aerobic base building rewards runners who think in seasons, not weeks. The restraint you practice here determines how resilient you’ll be when training becomes demanding. By progressing gradually, respecting recovery, and resisting the urge to accelerate the process, you build a foundation that supports not just one race—but years of consistent running.