When Long Runs Stop Building Endurance

Long runs hold a special place in distance training. They feel foundational, almost unquestionable. If endurance is the goal, then more time on feet must always be better—right?

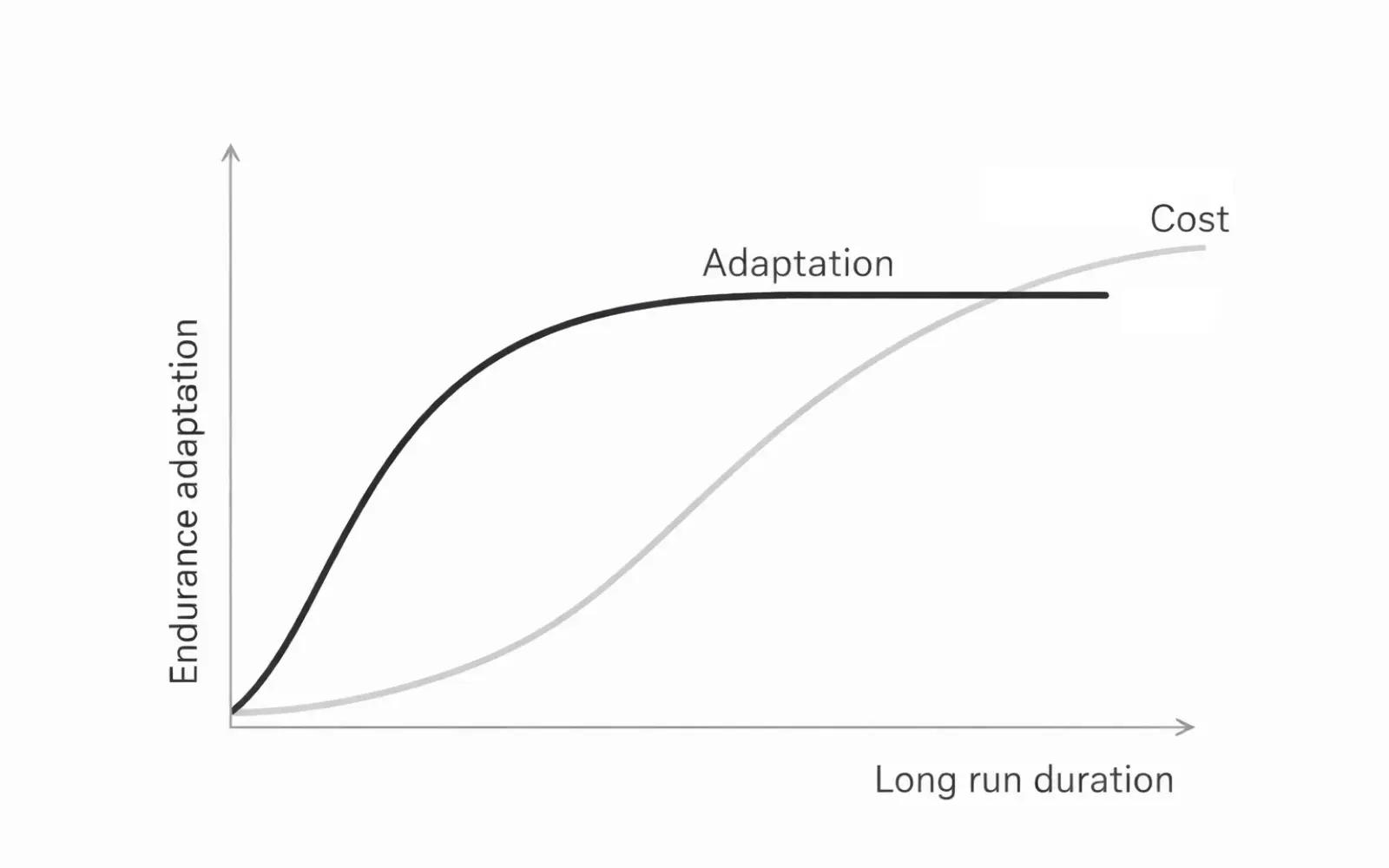

Most runners never challenge that assumption. And for a long time, they don’t need to. Long runs do work. They build aerobic capacity, improve fuel use, and condition the body for sustained effort. But like every training stimulus, their return is not infinite. Quietly, without a clear breaking point, long runs can stop building endurance and start extracting more than they give back.

This shift doesn’t announce itself with injury or collapse. It shows up as stalled progress, heavier legs, and training weeks that feel harder without feeling more effective.

Why long runs became untouchable

The logic behind long runs is sound. Endurance adaptations respond to prolonged aerobic stress. Spend more time running, and the body learns to deliver oxygen more efficiently, rely more on fat, and tolerate sustained output.

Because these adaptations accumulate slowly, runners tend to treat duration as the safest lever to pull. Pace can fluctuate. Workouts come and go. But the long run remains the weekly constant—the anchor.

The problem isn’t the long run itself. It’s the assumption that duration always equals stimulus, regardless of context.

What endurance actually adapts to

Endurance is not built by time alone. It emerges from a balance between signal and recovery.

During a well-executed long run, the body receives a strong aerobic signal:

- Mitochondria are stimulated to grow and function more efficiently

- Capillary networks expand to support oxygen delivery

- Fuel utilization shifts toward greater efficiency

But these adaptations don’t happen during the run. They happen afterward, when the system has enough resources to rebuild.

When fatigue grows faster than the body’s ability to absorb the signal, the run still feels demanding—but it stops producing proportional returns.

The quiet tipping point

There is no universal mileage or time limit where this happens. Instead, the tipping point is defined by cost.

As long runs extend beyond what the runner can reasonably recover from, several things begin to change:

- Pace drifts late in the run despite steady effort

- Neuromuscular control fades, even if breathing feels manageable

- Fueling keeps the run going but masks accumulating fatigue

- Recovery stretches into days instead of hours

At this point, the long run is no longer just an aerobic stimulus. It becomes a drain on the week that follows. Easy runs feel dull. Workouts lose sharpness. Training density drops—not because the runner is doing less, but because the system is carrying more fatigue forward.

This is where endurance stops compounding.

Why longer often feels more productive

Part of the challenge is psychological. Long runs reward completion. Finishing a demanding session creates a strong sense of progress, even when the physiological return is small.

There’s also a cultural weight to long runs. They are treated as proof of commitment, resilience, and readiness. Shortening or reshaping them can feel like backing away from the work, even when the outcome improves.

Because the cost shows up later—in the form of flat weeks rather than failed runs—it’s easy to miss the connection.

Signs a long run is no longer building endurance

The most reliable signals don’t come from the long run itself. They appear in the days around it.

Common indicators include:

- Easy runs feeling disproportionately heavy mid-week

- Needing extra recovery days after otherwise routine training

- Losing pace control late in the run without clear external cause

- Feeling mentally resistant to the next week’s workload

None of these mean the runner is weak or underprepared. They suggest that the stress is no longer landing cleanly.

Getting the benefit back without running less

The solution is not automatically a shorter long run. It’s a better-shaped one.

Endurance responds well to:

- Consistent long-run rhythm rather than constant extension

- Alternating stress weeks instead of stacking maximal efforts

- Long runs that finish feeling complete, not depleted

In many cases, improving endurance comes from increasing density—how well the week supports adaptation—rather than pushing the longest session further.

The long run should support the rest of training, not dominate it.

Endurance is cumulative, not maximal

Long runs are powerful because they work quietly over time. Their value lies in repetition, not heroics.

When a long run leaves the system stronger, the following week builds on it. When it leaves the system empty, progress pauses—even if the mileage looks impressive on paper.

Endurance grows best when stress is absorbed, not merely survived.