Lactic Acid in Distance Running: What Lactate Really Tells You About Effort and Fatigue

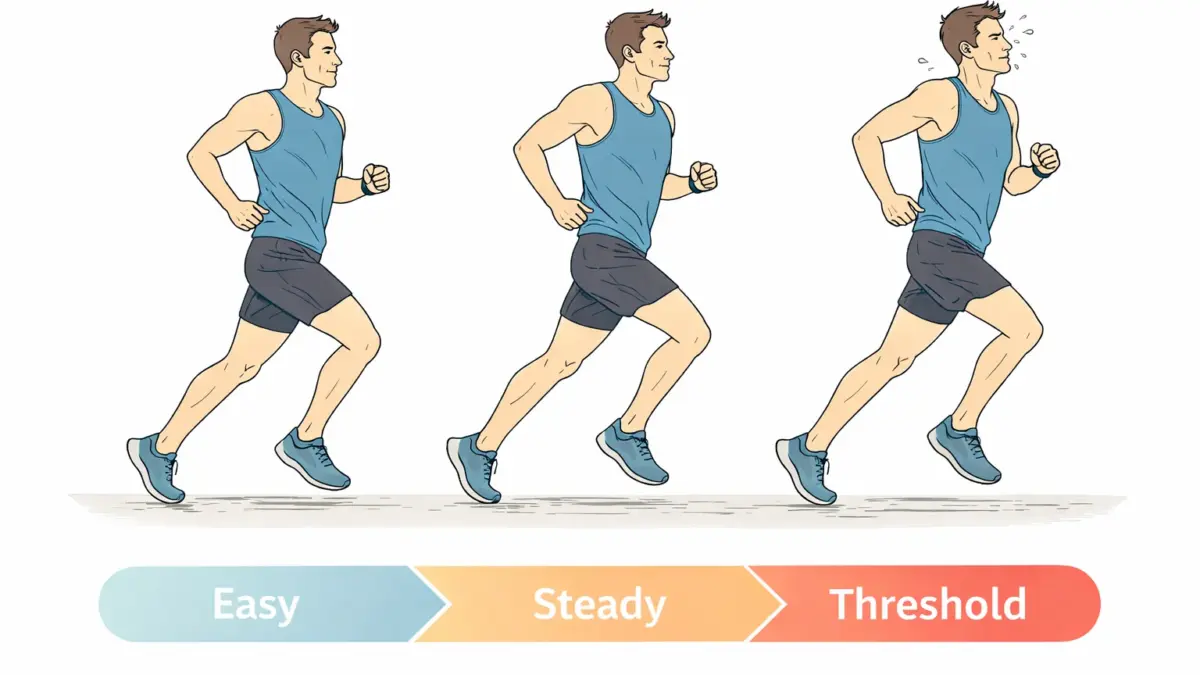

Easy efforts remain sustainable, while threshold intensity marks the point where fatigue begins to accumulate rapidly.

Few topics in running are as misunderstood as lactic acid. It is often blamed for burning legs, sudden fatigue, and the feeling that a pace has become unsustainable. In distance running, however, lactate is not a sign of failure. It is a normal consequence of energy production and one of the most useful indicators of effort intensity.

For amateur runners, understanding how lactate behaves can clarify pacing decisions, explain why certain efforts feel harder than others, and bring more structure and purpose to training.

What Lactic Acid Really Is

Running demands a continuous supply of energy to working muscles. This energy is produced by breaking down carbohydrates and fats. When oxygen delivery is sufficient, most of this process happens aerobically and can be sustained for long periods.

As pace increases, energy demand rises faster than oxygen availability. The body then relies more on anaerobic pathways. One result of this process is the production of lactate—often referred to as lactic acid in everyday language, although lactate is the form that actually circulates and is reused by the body.

Importantly, lactate itself is not harmful. It is a valuable fuel that can be transported to other muscle fibers, the heart, or the liver and converted back into usable energy. The familiar burning sensation during hard running is primarily linked to the accumulation of hydrogen ions, which interfere with muscle contraction, not to lactate itself.

Lactate During Easy and Hard Running

Lactate is produced at all running intensities, even during very easy runs. The key difference is how effectively the body clears it.

At low intensities, lactate production and clearance remain balanced. Blood lactate levels stay low and stable, which is why easy running feels controlled and sustainable.

As intensity increases, lactate production begins to exceed clearance. For a while, the body can manage this imbalance. Eventually, however, lactate and hydrogen ions accumulate faster than they can be processed, and fatigue rises rapidly. This transition marks a critical boundary in endurance performance.

Understanding the Lactate Threshold

The lactate threshold refers to the highest intensity at which lactate can still be cleared at roughly the same rate it is produced. Beyond this point, fatigue accelerates quickly.

For distance runners, lactate threshold is more relevant than maximum speed or even maximal oxygen uptake. It represents the effort level that separates controlled endurance from rapidly accumulating fatigue.

In practical terms, lactate threshold often feels like:

- A “comfortably hard” effort

- A pace that can be sustained for about 40–60 minutes

- Deep, rhythmic breathing that remains controlled but focused

Runners with a higher lactate threshold can maintain faster paces with less physiological stress. Two runners with similar fitness may perform very differently in races simply because one can operate closer to their maximum capacity without crossing this threshold.

Why Lactate Matters for Amateur Runners

Lactate is not just a laboratory concept. It has direct implications for everyday training and racing.

Pacing mistakes in races often come from unknowingly running above lactate threshold early on. What feels manageable in the first kilometers can become unmanageable later, not because fitness is lacking, but because intensity was misjudged.

From a training perspective, many of the most effective endurance adaptations occur near the lactate threshold. Spending too much time far above it leads to excessive fatigue. Staying too far below it limits stimulus. Understanding this balance helps runners train more consistently and recover better between sessions.

Training to Improve Lactate Threshold

The body adapts when it is exposed to repeated, controlled stress. Specific workouts encourage muscles to produce less lactate at a given pace and improve the body’s ability to clear and reuse it.

Tempo Runs

Tempo runs are the foundation of lactate threshold development. These are sustained efforts, typically lasting 20–40 minutes, run just below or around threshold intensity.

They teach the body to tolerate discomfort without tipping into exhaustion and improve metabolic efficiency at race-relevant paces.

Interval Training

Intervals run slightly above threshold intensity push the lactate system further. Shorter repetitions, combined with controlled recovery, allow runners to accumulate time at high effort without losing form or control.

Because these sessions are demanding, they are best used sparingly, especially by recreational runners balancing training with limited recovery time.

Long Runs With Steady Segments

Including moderate or steady segments within long runs trains the body to manage lactate under fatigue. This is particularly valuable for half marathon and marathon preparation, where maintaining pace late in the race depends on efficient lactate handling.

Common Misconceptions About Lactic Acid

Several long-standing myths still surround lactate:

- Lactate does not cause delayed-onset muscle soreness.

- Lactate is not a waste product; it is recycled energy.

- Actively “flushing out” lactate after a run is less important than overall aerobic fitness and recovery quality.

Modern exercise physiology views lactate as a messenger that reflects intensity and metabolic demand, not as a toxin to eliminate.

A More Useful Way to Think About Lactate

For distance runners, lactate is best understood as feedback. Rising lactate levels signal increasing intensity. Learning how different effort levels feel—easy, steady, threshold, and hard—builds pacing awareness that is often more reliable than numbers alone.

With consistent training, these sensations shift. Paces that once felt demanding become controlled. That shift reflects real endurance development, not because lactate disappears, but because the body becomes better at managing it.

Sources & Further Reading

- Brooks, G. A. – The Lactate Shuttle Theory

- Billat, V. – Lactate Threshold Concepts in Endurance Running

- American College of Sports Medicine – Endurance Exercise Physiology

- Seiler, S. – Intensity Distribution in Endurance Training

Lactic acid is not something to outrun or eliminate. It is part of the body’s adaptive system, guiding how fast, how long, and how often a runner can push. For distance runners, understanding lactate is less about chemistry and more about recognizing where sustainable effort ends—and how consistent training gradually moves that boundary forward.