How to Improve Cadence Without Forcing It

For most runners, cadence is not something that changes easily. It’s deeply embedded in movement patterns shaped by anatomy, coordination, and years of repetition. Trying to “fix” it directly—by staring at a watch or chasing a target number—often creates tension, inefficiency, and frustration.

The goal is not to manufacture a new cadence. It’s to remove the reasons cadence breaks down.

Start by redefining what “improvement” means

Improving cadence does not usually mean:

- Adding 10 steps per minute

- Matching an elite runner’s number

- Holding an artificially high rhythm

In endurance running, improvement usually looks like:

- Less cadence drop late in long runs

- Smoother rhythm under fatigue

- Shorter ground contact without rushing

- A cadence that emerges rather than one that’s imposed

If cadence becomes more stable and resilient, it has improved—even if the number barely moves.

Improve the conditions, not the cadence itself

Cadence responds to mechanics. Change the mechanics, and cadence often follows.

Focus on three foundational elements:

Posture

A tall, relaxed posture with a slight forward lean from the ankles allows the legs to cycle more freely. Collapsed posture almost always leads to longer strides and lower cadence.

Foot placement

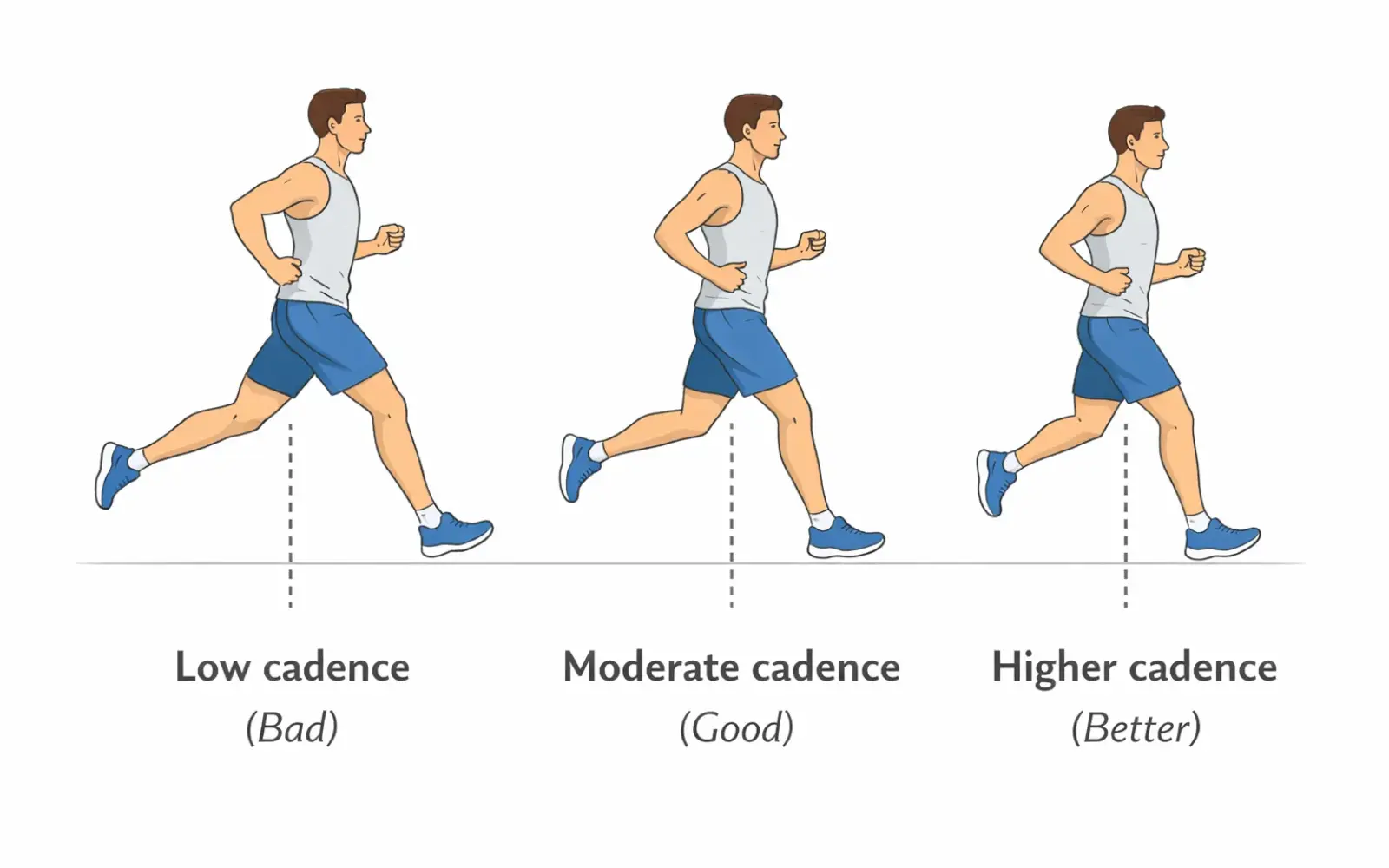

Landing closer to your center of mass reduces braking forces. When overstriding decreases, cadence often rises naturally—without conscious effort.

Arm swing

Arms set rhythm. Compact, relaxed arm movement supports quicker leg turnover without muscular tension.

None of these require thinking about cadence. They simply create space for it to self-organize.

Use short, controlled cadence exposure

Cadence responds better to brief exposure than constant monitoring.

Instead of running entire workouts at a “target” cadence:

- Insert 20–30 second segments of slightly quicker, lighter steps

- Stay relaxed, not fast

- Return to normal running immediately

This trains neuromuscular coordination without overwriting natural rhythm. Over time, the nervous system keeps what’s useful and discards what’s not.

Let strides do the work for you

Strides are one of the most effective—and least forced—ways to influence cadence.

Short accelerations of 15–25 seconds:

- Naturally increase cadence

- Improve elastic recoil

- Reinforce efficient mechanics

Because strides are fast but relaxed, cadence increases as a byproduct of better movement—not conscious control. Two sessions per week are enough for most runners.

Train cadence where it actually matters: late

Cadence rarely fails early in a run. It fails under fatigue.

To make cadence more durable:

- In long runs, focus on rhythm in the final 15–20 minutes

- Do not chase pace

- Accept slowing speed, but protect form and step rhythm

This is where cadence training becomes race-relevant. Stability under fatigue transfers far better than early-run perfection.

Avoid the common traps

Cadence work goes wrong when it becomes rigid.

Avoid:

- Constant metronome use during long runs

- Large, sudden cadence increases

- Comparing your cadence to others

- Treating cadence as a fix for unrelated issues

Cadence is sensitive. It responds best to subtle nudges, not force.

A realistic expectation

For most endurance runners:

- A 2–5% change is meaningful

- Stability matters more than peak values

- Improvements show up late, not early

If your cadence holds together when effort rises and fatigue accumulates, you’ve succeeded—even if the watch barely notices.

Where this leaves cadence training

Cadence improves best when it’s treated as a symptom, not a target. When mechanics clean up, rhythm stabilizes. When rhythm stabilizes, efficiency lasts longer.

The paradox is simple: the less you try to force cadence, the more likely it is to improve.

That’s not passive training. It’s precise, patient, and well-timed—exactly what endurance running rewards.