Energy Crashes in Distance Running: Why They Happen — and How to Stay Ahead of Them

Energy Crashes in Distance Running: Why They Happen — and How to Stay Ahead of Them

Energy crashes are often framed as a marathon problem. A dramatic moment late in the race, legs turning heavy, pace unraveling, survival mode engaged. But for many runners, the most confusing crashes don’t happen at mile 20. They happen much earlier—sometimes halfway through a hard half marathon, sometimes during a long progression run—when fitness feels solid and preparation seemed sufficient.

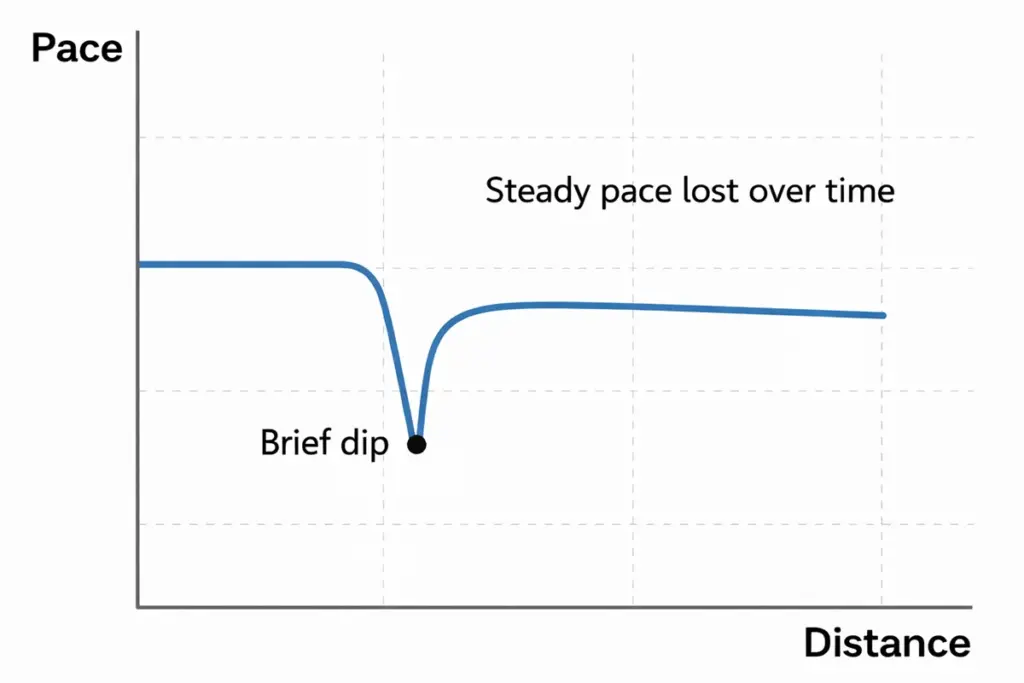

These moments are brief but costly. A few seconds of disorientation. A subtle loss of coordination. A pace that slips just enough to turn a good race into a frustrating one. Not a total collapse, but enough to leave you wondering what went wrong.

Understanding these crashes requires moving past the idea of “the wall” and looking instead at how energy supply, intensity, and timing interact under real racing conditions.

Energy Crashes Are a Spectrum, Not a Single Event

Not every energy failure looks the same.

At one end of the spectrum is the classic glycogen bonk: complete carbohydrate depletion after prolonged effort. At the other end are transient energy dips—short-lived but disruptive moments caused by a mismatch between energy demand and energy availability.

These milder crashes are common in:

- sub-90 half marathons

- long runs with extended tempo sections

- races run close to lactate threshold

They don’t always come with heavy breathing or obvious muscular fatigue. Instead, they show up as:

- brief dizziness or mental fog

- a feeling of losing control of stride

- delayed reaction or coordination

- an abrupt drop in pace without a clear muscular reason

The body isn’t empty. It’s under-supplied at a critical moment.

What’s Actually Happening Physiologically

During high-intensity endurance running, carbohydrate use dominates. Even well-trained runners with strong fat-oxidation capacity rely heavily on glycogen when effort rises near threshold.

In a hard half marathon, glycogen stores are rarely fully depleted. But glucose availability in the blood can still fall below what the brain and working muscles expect, especially when:

- no carbohydrates are consumed during the race

- early pacing is slightly aggressive

- carbohydrate intake in the days before was marginal

- hydration is just low enough to affect circulation

The result is not full exhaustion, but a temporary energy bottleneck. The brain senses a shortage before the muscles do, leading to disorientation, loss of rhythm, and impaired motor control.

This is why some runners experience energy crashes as seconds-long events that cascade into minutes of lost time.

Why Half Marathoners Are Especially Vulnerable

Many runners are told they don’t need fueling for a half marathon. That advice assumes moderate pacing and conservative intensity.

A runner targeting just under 1:30 is doing something very different:

- sustaining effort close to lactate threshold

- burning carbohydrates rapidly

- operating with little metabolic margin

At this intensity, skipping fueling isn’t neutral—it’s a gamble. Even a small carbohydrate intake can stabilize blood glucose and protect neuromuscular control late in the race.

This is why experienced, well-trained runners can still crash despite being “fit enough.” Fitness raises the ceiling, but fueling determines whether you can use it all the way to the line.

Real-World Example: A Non-Classic Energy Crash

A well-trained runner targeting a sub-1:30 half marathon raced twice without in-race carbohydrate intake, expecting fitness alone to sustain the effort. In both races, a sudden energy dip appeared around 11–12 km: brief disorientation, slight loss of stride control, and an abrupt pace drop. The sensation passed within seconds, but the damage accumulated over the following kilometers, costing several minutes overall.

Importantly, this outcome was not inevitable. With more deliberate preparation—stronger carbohydrate availability going into the race and better alignment between pacing and fueling—the same effort could likely have been completed without gels. This was not full glycogen depletion, but a transient energy shortfall exposed by high intensity and limited metabolic margin.

The Hidden Cost of Pacing Errors

Energy crashes are rarely caused by one mistake. But pacing often accelerates everything else.

Starting slightly too fast increases carbohydrate burn rate early, narrowing the window for error later. The body may feel smooth and controlled at 5 km, but by 10–12 km the accumulated cost shows up—not as fatigue, but as instability.

This is where many crashes begin: not with heavy legs, but with subtle loss of efficiency that compounds quickly.

How to Stay Ahead of an Energy Crash

Preventing energy crashes isn’t about avoiding discomfort. It’s about managing supply before demand overwhelms it.

Train the Metabolic System

Long runs at controlled effort improve fat utilization and spare glycogen. This doesn’t eliminate carbohydrate needs, but it delays the point where shortages matter.

Fuel Earlier Than Feels Necessary

For hard efforts lasting longer than an hour, begin carbohydrate intake early—before signs of fatigue appear. A small dose can prevent disproportionate consequences later.

Hydration Is Part of Energy Delivery

Even mild dehydration reduces blood volume, making glucose delivery less efficient. Electrolytes matter not for cramp prevention alone, but for maintaining circulation and neural function.

Pace With Intent, Not Emotion

Threshold-adjacent racing punishes small pacing errors. Discipline early protects energy availability later.

Learn the Early Signals

Experienced runners often sense the warning signs: a dip in mood, lightheadedness, slight chills, loss of rhythm. These are cues to act, not push through.

Reframing the Experience

Energy crashes are not failures of toughness or preparation. They’re feedback.

They reveal where effort, fueling, and pacing were misaligned—not dramatically wrong, just wrong enough to matter. The lesson isn’t to fear hard racing, but to support it better.

When runners learn to recognize these moments and adjust proactively, crashes stop being mysterious. They become manageable, predictable, and increasingly rare.

And when that happens, strong finishes stop feeling like luck—and start feeling earned.