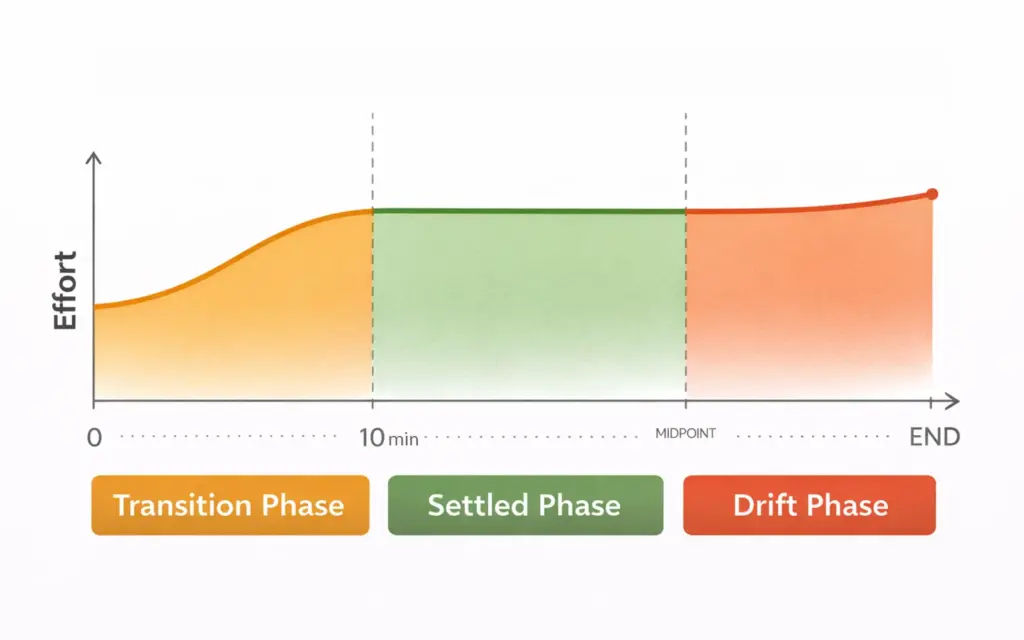

The Middle of the Run: Why the First 10 Minutes and the Last 10 Minutes Feel So Different

Every run has phases.

Even when pace stays constant and terrain doesn’t change, your body does. The first ten minutes rarely feel like the middle. And the last ten minutes rarely feel like either.

Most amateur runners interpret these shifts emotionally — “I’m sluggish today” or “I’m fading.” But what feels like mood or motivation is often physiology unfolding in predictable stages.

Understanding these phases changes how you interpret effort — and how you pace your runs.

Phase One: The Transition (Minutes 0–10)

The beginning of a run often feels awkward.

Breathing seems slightly labored. Stride feels mechanical rather than fluid. Legs may feel heavy even at an objectively easy pace.

This isn’t a lack of fitness. It’s adjustment.

Oxygen kinetics catching up

When you start running, energy demand rises immediately. Oxygen delivery does not.

For the first few minutes, the body relies more heavily on anaerobic contribution while the cardiovascular system ramps up. As blood flow increases and muscle oxygen extraction improves, effort begins to stabilize.

On easy runs, this transition is mild — but perceptible.

Neuromuscular calibration

Motor units must synchronize to the new task. Even if you run daily, each session begins with recalibration.

Stride frequency, tendon stiffness, and joint angles subtly adjust. Until coordination stabilizes, running feels slightly inefficient.

This is why the same pace can feel harder in minute three than in minute fifteen.

Phase Two: The Settled Rhythm (The Middle)

Somewhere between minute ten and the midpoint of your run, something shifts.

Breathing finds a pattern. Stride smooths out. Effort perception decreases even if pace remains unchanged.

This is the most mechanically economical phase of the run.

Elastic efficiency

Tendons behave more predictably once warmed and repeatedly loaded. The stretch–shortening cycle becomes consistent. Energy return feels smoother.

The nervous system stops adjusting and starts repeating.

Stable cardiovascular state

Heart rate plateaus relative to intensity. Oxygen delivery matches demand more precisely. Metabolic cost per stride becomes more efficient.

This is where “easy pace” actually feels easy.

Importantly, this phase does not last indefinitely.

Phase Three: The Drift (Final Segment)

Late in the run, subtle fatigue appears.

Pace may be steady. Heart rate may be only slightly elevated. But stride sharpness begins to soften.

This is not collapse. It’s drift.

Cardiovascular drift

Even at constant speed, heart rate gradually rises over time due to dehydration, rising body temperature, and cumulative metabolic demand.

The effort feels marginally harder despite unchanged pace.

Neuromuscular fatigue

Motor unit firing becomes slightly less synchronized. Ground contact time may increase imperceptibly. Tendon recoil becomes less crisp.

These changes are small but meaningful. They often appear before dramatic fatigue.

The key insight: the last ten minutes are mechanically different from the middle — even when your watch says nothing has changed.

Why This Matters for Amateur Runners

Understanding these phases prevents misinterpretation.

- If the first minutes feel awkward, it doesn’t mean you’re unfit.

- If the final minutes feel slightly heavier, it doesn’t mean you’re failing.

- If the middle feels smooth, that’s not accidental — it’s physiological alignment.

This awareness also improves pacing.

Many runners push too early because the beginning feels uncomfortable and they want to “get into it.” Others misread late-run drift as a signal to stop when they are simply entering normal fatigue progression.

Recognizing these stages helps you respond calmly rather than react emotionally.

Training Implications

You can use these phases intentionally:

- Allow the first ten minutes to unfold without judgment.

- Notice when rhythm stabilizes — that’s your mechanical baseline.

- Observe subtle late-run changes without immediately adjusting pace.

Over time, you may find the transition phase shortens and the settled rhythm extends. That is a quiet marker of aerobic durability.

The body does not experience a run as a single block of time. It moves through stages.

When you learn to recognize them, pacing becomes more intuitive, and effort becomes less mysterious.

And that changes how every run feels — from the first step to the last.